Explore the Isle of Man's 10 Marine Nature Reserves (MNRs) on #MarineMondays. In the penultimate article of the series, and the second on the West Coast MNR, Dr Peter Duncan, Senior Marine Environment Officer for DEFA, writes about dragons, monsters - and the pioneering work of a young marine biologist:

The West Coast MNR begins at the Point of Ayre and, according to the Northern Lighthouse Board, the lighthouse is technically inside this MNR. This feels important for two reasons.

The first reason is the historic significance of this lighthouse; the oldest operational one on the Island (lit in 1818) and one of two lights on the Isle of Man designed and built by that most famous lighthouse engineer, Robert Stevenson.

His other one is the Lower Lighthouse on the Calf of Man, also completed in 1818.

As a wee aside, his sons, David and Thomas Stevenson subsequently designed the Chicken Rock lighthouse, completed in 1874 (and first lit in 1875), and it was Thomas Stevenson who helped ‘design’ his own son, the Scottish writer, Robert Louis Stevenson. More of him later.

The 1818 Point of Ayre lighthouse in sunshine

The second reason is a little less practical. To me, lighthouses have a certain mystery and romance; marking an area of maritime hazard, sometimes a boundary between safety and danger, the known and the unknown. 'Beyond this point there be dragons!’

The ‘mysterious’ Point of Ayre lighthouse in shadow

The name Point of Ayre comes from the old Norse word Eyrr, or gravel beach, and indeed, the glacial moraines (rounded sands, gravel, pebbles and boulders), brought down by ice from the frozen north, are what formed this part of the Island.

The currents that swirl around the top of the Island shuffle this odd collection of foreign rocks and fossils, creating the beaches of the Ayres and the numerous shifting sand banks off the north-east coast, and bring nutrients to the horse mussel reefs of Ramsey Bay, the fish shoals that support the breeding seabirds and fuel to the food chains that, every so often, provide evidence of ‘dragons’.

A member of the public dropped off this dragon claw (ok, its a lobster claw) a few years ago, and indicates a total length of maybe a metre long and an age of perhaps 30-50 years. This really is a place of monsters!

Giant lobster claw from Point of Ayre

Travelling south-westwards along one of the least-populated parts of the Island, perhaps adding to the mystery of the area, the dominant marine feature is ‘The Targets’, a former bombing range and munitions disposal area associated with the old RAF base at Jurby Head.

Back in 1839, the 24-year-old Edward Forbes, who became the Island’s most famous marine biologist, published the results of a seven-year study (1832-1839) on ‘a scallop bank five miles off Ballaugh and 20 fathoms (37 m) deep’; the present day ‘Targets’.

During his study, he recorded an abundant molluscan fauna, including, whelks, horse mussels, native oysters and five different species of scallop.

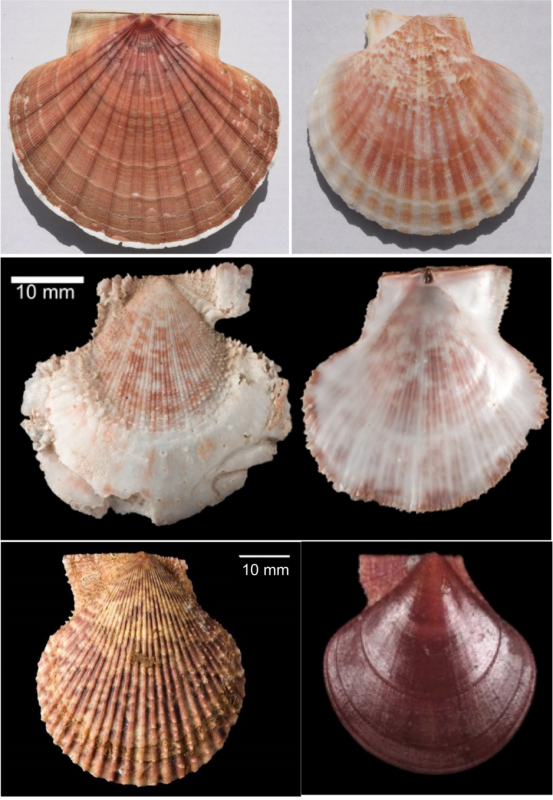

The five scallop species reported from Targets in 1939. Left to right, top to bottom; king scallop (Pecten maximus), queen scallop (Aequipecten opercularis), hunchback scallop (Talochlamys pusio), spiny scallop (Mimachlamys varia), tiger scallop (Palliolum tigerinum)

While three of those original mollusc species, king scallop, queen scallops and whelk, still exist there today, and are now the basis of the Island’s main fisheries, we have ‘lost’ both horse mussels and flat oysters from the area in the last 181 years due to various human activities.

Two of the other scallop species recorded in the study live in close association with horse mussel reefs, so if we lose that habitat/species, we also lose the other species that live there.

So how do we achieve protection of current and future fisheries and at the same time ensure that Forbes’ other species are around for the next 181 years, and, maybe, welcome back the missing ones? Why, with a Marine Nature Reserve, of course.

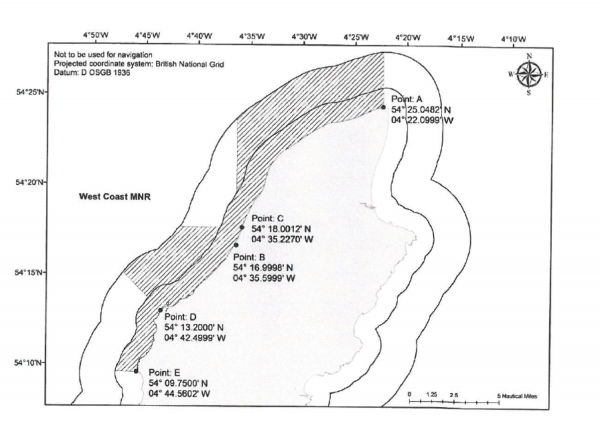

Looking at the map of the West Coast MNR, there is evidence of compromise to represent the multiple interests in the area, with the eventual boundaries having been negotiated with Manx fishermen whose support has been so important (and unique) for the development of our MNR network.

West Coast MNR map

Such a large sea area could not exclude all scallop fishing, so the main Targets ground remains outside the reserve (hence the ‘triangular bite’ in the map), although pot fishing is permitted within the whole MNR. As discussed in earlier weeks, the separation of different fisheries is one benefit, but the presence of un-fished stocks within the reserves also helps support and secure the future of the fisheries outside.

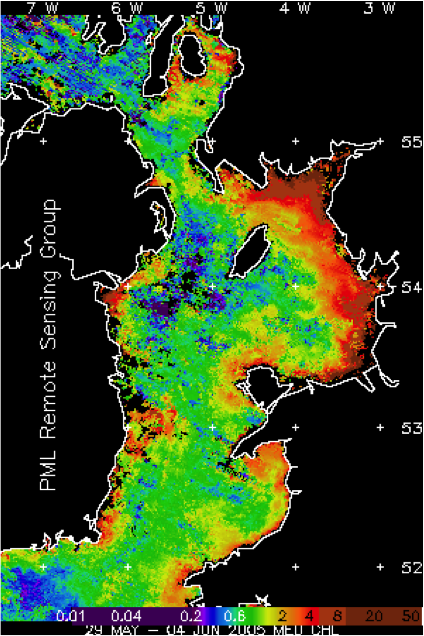

The Targets fishing ground, and the MNR, also benefit from natural hydrographic conditions as a frontal system, where north-moving, colder oceanic water meets westerly-moving warmer water from the eastern Irish Sea, occurs over the area. The red/orange area of eastern Irish Sea water can be seen spreading round the north of the Island, and down towards the Targets, in the following map.

Chlorophyll (phytoplankton) concentrations around the Isle of Man; note the ‘red/orange’ waters extending around the north of the Island

This convergent front concentrates the nutrients, plankton and scallop larvae contained in the water currents, and the larvae regularly settle on the Targets ground, explaining both its fishing consistency and long-term resilience.

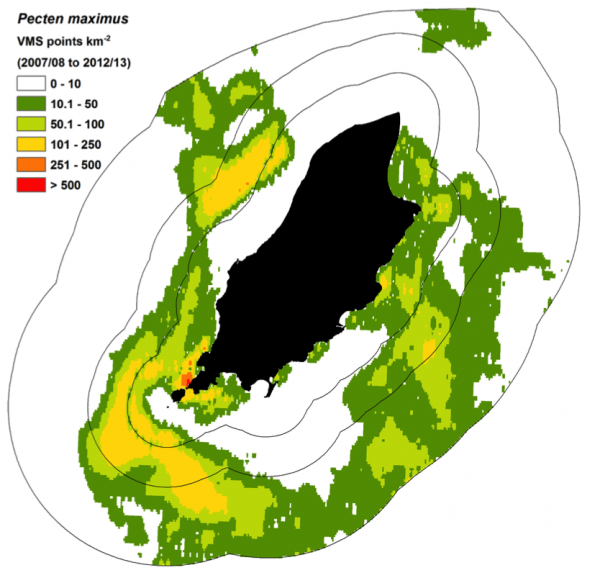

The scallop fleet on the Targets fishing ground

Scallop fishing activity map – see image title for caption

Equally importantly, though, is the obvious conclusion that our sea areas are connected – the scallop larvae that populate Targets originate from Ramsey Bay, from the south and from Targets itself. What we do in one place affects others, and so a holistic or joined-up approach is required for our environmental and resources management.

The opportunity to help promote and progress this concept around the Island is why I feel lucky to be doing the job that I do.

To get back (more or less) to where we started, Robert Louis Stevenson remarked that 'it is perhaps a more fortunate destiny to have a taste for collecting shells than to be born a millionaire'.

Colour variations of Manx king scallop shells

Colour variations of Manx queen scallop shells

In context, he was suggesting that wealth and material acquisition should, at the very least, be tempered by some more fundamental considerations of life.

The MNRs help provide the balance between economic considerations and environmental, and at the same time mutually support each other. This is the basis of sustainability and at the heart of Biosphere.

References:

Edward Forbes (1839) XXIII. On a shell-bank in the Irish Sea, considered zoologically and geologically. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 4:24,217-223.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/20335#page/243/mode/1up

To find out more about the Isle of Man's Marine Nature Reserves, click here.